Opinion

On the night Breonna Taylor died, Detective Brett Hankison stood outside her apartment and blindly fired 10 rounds through a bedroom window and a sliding glass door, both of which were covered by blinds and curtains.

Based on that reckless conduct, a federal jury in Louisville, Kentucky, last week convicted Hankison of willfully violating Taylor’s Fourth Amendment rights under color of law.

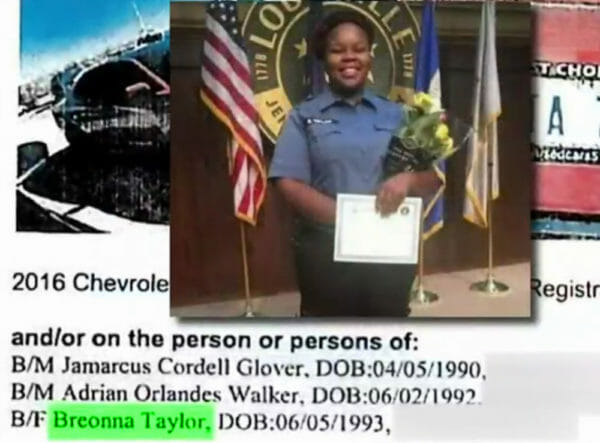

Hankison did not kill Taylor, and his baffling behavior was just one of many things that went wrong before, during, and after the deadly March 2020 raid, including a misleading and legally deficient search warrant affidavit that tied the 26-year-old EMT to drug dealing based on little more than guilt by association.

But Hankison’s case vividly illustrates the difficulty of holding police officers criminally liable for abusing their powers.

Hankison was fired three months after the raid. Acting Police Chief Robert Schroeder said the detective had “displayed an extreme indifference to the value of human life” by firing “wantonly and blindly” without “verifying any person as an immediate threat” or considering “any innocent persons present.”

An indictment approved by a Kentucky grand jury in September 2020 likewise charged Hankison with three felonies for “wantonly” discharging his weapon “under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to human life.” The charges were based on bullets that penetrated an apartment adjoining Taylor’s, endangering her neighbors.

In March 2022, a state jury, after deliberating for three hours, acquitted Hankison of those charges, suggesting how much slack jurors tend to give police officers who say they used deadly force in response to a perceived threat. Five months later, Hankison was indicted on two federal charges, alleging that he violated Taylor’s rights as well as her neighbors’.

Last year, a federal judge declared a mistrial on those charges because the jury failed to reach a verdict. During his second federal trial, Hankison again testified that he was trying to help two fellow officers inside Taylor’s apartment, Sgt. Jonathan Mattingly and Detective Myles Cosgrove, thinking they were under sustained fire.

Hankison was wrong about that. When police broke into the apartment around 12:45 a.m., Taylor’s boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, who later said he had no idea the intruders were cops, grabbed a handgun and fired a single round, striking Mattingly in the leg.

In response, Mattingly and Cosgrove fired a total of 22 rounds down a dark hallway, where Taylor, who was unarmed, was standing near Walker. Hankison testified that he mistook his colleagues’ gunfire for rounds from an AR-15 rifle that was “making its way down the hallway and executing everybody.”

Even so, Hankison’s response is hard to fathom. “He did exactly what he was supposed to do,” defense attorney Don Malarcik told the jurors during his closing argument. “He was acting to save lives.”

Not so, said Assistant U.S. Attorney Michael Songer. Hankison “violated one of the most fundamental rules of deadly force,” Songer told the jury. “If they cannot see the person they’re shooting at, they cannot pull the trigger.”

According to Yvette Gentry, Louisville’s former interim police chief, Cosgrove — who fired 16 rounds into the apartment, including the one that killed Taylor — did something similar. Gentry canned Cosgrove in December 2020, saying he had fired “in three distinctly different directions,” which indicated he “did not identify a specific target.”

An investigation by former Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron nevertheless concluded that both Cosgrove and Mattingly had fired in self-defense, meaning criminal charges were not justified. So far, Hankison, who was found guilty of the charge involving Taylor but acquitted of the charge involving her neighbors, is the only officer directly involved in the raid to be convicted of a crime.

Federal charges are still pending against former Detective Joshua Jaynes, who wrote the search warrant affidavit, and former Sgt. Kyle Meany, who approved it. But it is not hard to see why Attorney General Merrick Garland suggests that “justice for the loss of Ms. Taylor is a task that exceeds human capacity.”

Read Related: Breonna Taylor: Another No-Knock Raid Legitimately Resisted by Armed Force

About Jacob Sullum

Jacob Sullum is a senior editor at Reason magazine. Follow him on Twitter: @JacobSullum. During two decades in journalism, he has relentlessly skewered authoritarians of the left and the right, making the case for shrinking the realm of politics and expanding the realm of individual choice. Jacobs’ work appears here at AmmoLand News through a license with Creators Syndicate.

from https://ift.tt/IvJzRf1

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment