Opinion

U.S.A. –-(Ammoland.com)- Many Second Amendment supporters have heard of the National Firearms Act (NFA) of 1934. It went into effect on 26 June, 1934. It was the first national gun law to have a substantially limiting effect. It was the first federal statute challenged in the Supreme Court on the basis of the Second Amendment, in United States v. Miller. The story of that challenge may be read, in short form, on an AmmoLand News article from 2013.

Far fewer people are familiar with the National Firearms Act of 1938. The NFA of 1934 was passed in Franklin Delano Roosevelt's (FDR) first term. The case that challenged it was set up in 1938, it is believed, to curb resistance to the National Firearms Act of 1938, passed in FDR's second term.

The infamous National Firearms Act of 1934 required commercial manufacturers to stamp serial numbers on machine guns, silencers, and short-barreled rifles and short-barreled shotguns manufactured from that date on.

Few people worried about the law because it only affected items that crossed state lines. Not many people owned machine guns or silencers; few crossed state lines with them or short-barreled rifles or shotguns. Because of concerns about constitutionality, the NFA of 1934 was a gun ban disguised as a tax. The transfer tax of $200 was equivalent to about $3,800 in 2018. It was prohibitive for all but the very well off. Consequently, it raised very little money.

The original target of the NFA of 1934 was to register and regulate the ownership of all handguns. Short barreled rifles and shotguns were included to prevent circumventing the regulation of handguns by cutting down rifles and shotguns. The National Rifle Association (NRA) was successful in stripping handguns from the bill. Because silencers, machine guns, short-barreled rifles, and shotguns were less commonly owned, the NRA did not contest that part of the law.

The progressives in the Roosevelt administration, especially Attorney General Homer Cummings, wanted to register all pistols and regulate all pistol sales. The attempt to do so in the 1934 NFA had failed. Another trial balloon to do so was proposed by Cummings in 1936 but failed to make headway.

The NFA of 1938 was different. It required federal licenses for commercial manufacture and sales of all firearms and firearms parts that were involved in interstate commerce or inside of federal territories which were not states. It was an incremental move toward federal control of all common firearms. Whether this was constitutional under the Second Amendment was disputed and debated.

In spite of thousands of objections to the passage of the NFA of 1938, it was passed and became law on June 30, 1938.

The FDR administration was looking for a test case to take to the Supreme Court, to establish federal regulation of firearms commerce as constitutional. Two months before the passage of the 1938 NFA, on 18 April 1938, two small-time criminals were arrested for “making preparation for armed robbery”, by Oklahoma and Arkansas state police. They had in their possession a short-barreled shotgun. They had traveled from Oklahoma to Arkansas. They were brought to Fort Smith, Arkansas.

One of them, Jackson “Jack” Miller, had been an informant and participant in a significant case involving the O'Malley gang. He was known to the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Arkansas, Clinton R. Barry. Barry saw an opportunity for an NFA of 1934 test case. He wired the Attorney General of the United States on 23 April 1938, explaining the importance of acting quickly, before the pair were let off on bail.

Miller was also known to the federal judge who had presided over the O'Malley case, Heartsill Ragon. Judge Heartsill Ragon was the 1930's version of Chuck Schumer, a strong proponent of restrictive federal gun law. He helped push through the New Deal for FDR before being rewarded with a federal judgeship in Arkansas.

The NFA case was given to Judge Heartsill Ragon. He appointed the defense counsel. He refused to accept a guilty plea.

Judge Ragon had the case he wanted, the defendants he wanted and the defense council he wanted. Judge Ragon then created the only defense for the case, his memorandum opinion.

On June 11, 1938 Miller and Layton demurred to the indictment, claiming that it presented insufficient evidence of a transfer requiring payment of a tax and challenging the constitutionality of the NFA under the Second and Tenth Amendments. Surprisingly, Ragon immediately issued a memorandum opinion sustaining the demurrer and quashing the indictment. He held that the NFA violates the Second Amendment by prohibiting the transportation of unregistered covered firearms in interstate commerce.

This position was diametrically opposite his stated opinion while a legislator. It did not include any facts or analysis to support the proposition.

The FDR administration appealed the case directly to the Supreme Court. With only the government's side of the case presented, the Court refused to strike down the law. The Miller decision was muddy and subject to interpretation.

Progressives used the Miller case to claim the Second Amendment did not protect an individual right. Progressive judges appointed by FDR and Truman came to dominate the federal appeals courts.

U.S. v. Miller was used to prevent challenges to the NFA of 1938. While Miller clearly implied that military arms were protected by the Second Amendment, FDR appointed judges ruled it did not.

In Cases v. United States, 1942, a three-judge panel on the First Circuit ruled it was unlikely Miller meant military arms were protected by the Second Amendment: From Cases:

Another objection to the rule of the Miller case as a full and general statement is that according to it Congress would be prevented by the Second Amendment from regulating the possession or use by private persons not present or prospective members of any military unit, of distinctly military arms, such as machine guns, trench mortars, anti-tank or anti-aircraft guns, even though under the circumstances surrounding such possession or use it would be inconceivable that a private person could have any legitimate reason for having such a weapon. It seems to us unlikely that the framers of the Amendment intended any such result.

The judges did not want military arms protected, so they ruled they were not protected.

All three judges on the First Circuit in Cases v. United States, John Mahoney, Calvert Magruder, and Peter Woodbury, were appointed by FDR.

The Supreme Court refused to hear another Second Amendment case until 2008.

The NFA of 1938 established the precedent the federal government could regulate the interstate commerce of common, ordinary firearms, as well as the sale of firearms in none-state territories. It established the precedent the federal government could create classes of people who were not allowed to purchase firearms across state lines. It established the notion of a federal license to commercially sell or manufacture ordinary firearms.

The NFA of 1938 was passed before the seminal Supreme Court decision of Wickard v. Filburn in 1942, when the nation was in the middle of World War II. Wickard is recognized as an inflection point at which virtually everything in the United States was considered to be affecting interstate commerce, and thus subject to regulation by the federal government. Still, interstate commerce and the limitation on government power held meaning. In police training in the late 1970's, I was taught interstate commerce had to cross state lines; and that criminal statutes were part of state powers, while federal power was not concerned with local criminal acts.

While people were concerned with the NFA of 1938, dealer's licenses were shall issue and only cost a dollar. Individuals who were not dealers could purchase firearms across state lines. In theory, all firearms parts were regulated. In practice, the regulation was minimal to non-existent.

No serial numbers were required except on machine guns, silencers, and short-barreled rifles and shotguns. It was illegal to remove the manufacturer's serial numbers, but manufacturers were not required to place serial numbers on the vast majority of firearms.

The 1938 NFA did not require record-keeping or pre-approval of any sales or manufacture, except for machine guns, silencers, and short-barreled shotguns and rifles.

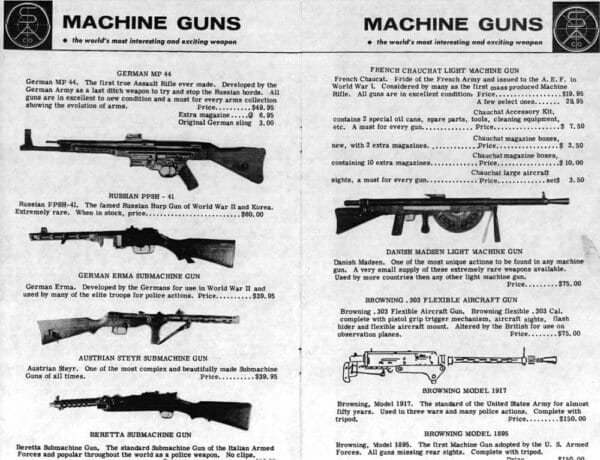

The FDR administration continued to float proposals for the registration of all firearms in the United States, but World War II intervened. AG Homer Cummings had retired in January of 1939. No one was pushing for keeping Americans from having guns in the middle of a war. After the war was won, millions of rifles, pistols, and shotguns, were purchased from powers all over the globe, and sold to the American people at bargain prices. It was a golden age for firearms collectors, hunters, and shooters. Crime was low. Guns were available over the counter for cash, and by mail order. If you wanted to purchase across state lines, from dealers, without hindrance, a Federal Firearms License (FFL) was easily obtained for a dollar. Many firearms enthusiasts obtained FFLs to ease firearms transactions.

Anti-tank cannon, anti-aircraft cannon, and their ammunition were advertised on the pages of the American Rifleman, and purchased by mail order. Only one crime was recorded where an anti-tank rifle was used. No one was injured.

The precedents of the 1934 NFA and 1938 NFA were the seeds of the infamous 1968 Gun Control Act (GCA). Again, the NRA mitigated the worst part of the bill and won a small reversal of earlier overreach.

It was argued that regulation of all firearms parts was burdensome and silly. There was no sense in regulating bolts, screws, and grips. A firearm was defined as the receiver that had the serial number. On handguns, the same part is called the frame. Firearms parts, except for the receiver or frame, could be commercially manufactured and sold without a firearms manufacturer's license. It was regarded as a commonsense approach.

Lyndon Johnson wanted full registration of all pistols. That provision was struck from the bill.

Significant new infringements were passed and became law with GCA 1968. All new firearms were required to have serial numbers. Federal dealers were required to record sales, personal information, make, model, and the newly required serial numbers. Purchases of firearms across state lines by individuals, except through federal dealers, were made illegal. More firearms and weapons were placed under strict controls. More categories of persons were prohibited from buying from federal dealers.

The NFA of 1934, the NFA of 1938, and the GCA of 1968 are all points on the slippery slope of ever more infringements on Second Amendment rights. Regarding the Second Amendment as outdated and irrelevant came with Progressive philosophy. Progressive philosophy holds the Constitution to be outdated and limits on government to be immoral.

It was dozens of Progressive judges appointed by FDR and later presidents which cemented the progressive view of a “living Constitution” into the American legal system.

President Trump is appointing dozens of originalist and textualist judges. Originalist and textualist judges believe in enforcing the original intent of the Constitution. As such, they will likely remove many “living Constitution” constructs and restore limits to federal power.

About Dean Weingarten:

Dean Weingarten has been a peace officer, a military officer, was on the University of Wisconsin Pistol Team for four years, and was first certified to teach firearms safety in 1973. He taught the Arizona concealed carry course for fifteen years until the goal of Constitutional Carry was attained. He has degrees in meteorology and mining engineering and retired from the Department of Defense after a 30-year career in Army Research, Development, Testing, and Evaluation.

The post 1934 NFA, the Failed 1938 NFA, Miller, and the Regulation of Gun Parts appeared first on AmmoLand.com.

from https://ift.tt/2SZWGYg

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment